Defining Hindudharma: The Tānūnaptra Metaphor

How can we understand Hindudharma’s unity? Why is it not artificial but theologically and divinely meaningful?

At the outset it must be stated that this piece is not an exercise in discursive reasoning, or some carefully worked argument based on some first principles or axioms. The “reasoning” here is rather analogous and more amenable to those with the intuition to grasp ideas through analogies.

In the Somayāga, following the Ātithyeṣṭi (where the god Soma is received as a royal guest), we have the Tānūnaptra rite, where the leftovers of the ājya (ghee) from Ātithyeṣṭi in the dhruva ladle are cut out in either four or five portions and then fed into a special camasa (a cup), known as the Tānūnaptra-camasa. The Ṛtvijaḥ (the sixteen priests of the Soma sacrifice) and the Yajamāna will touch this ghee, with an undertaking to not betray one another and act for mutual benefit.

In the Taittirīya-Saṃhitā, we have an account of the story behind the Tānūnaptra rite as follows:

6.2.2.1

“devāsurāḥ saṃyattā āsan

te devā mitho vipriyā āsan

te ‘nyo’nyasmai jyaiṣṭhyāyātiṣṭhamānāḥ pañcadhā vy akrāmann agnir vasubhiḥ somo rudrair indro marudbhir varuṇa ādityair bṛhaspatir viśvair devais

te ‘manyanta | asurebhyo vā idam bhrātṛ vyebhyo radhyāmo yan mitho vipriyāḥ smo yā na imāḥ priyās tanuvas tāḥ samavadyāmahai tābhyaḥ sa nir ṛchād yaḥ||”

“naḥ prathamo ‘nyo’nyasmai druhyād iti

tasmād yaḥ satānūnaptriṇām prathamo druhyati sa ārtim ārchati”

The Deva-s and Asura-s were in conflict.

They, the Deva-s, were mutually hostile.

They, one another’s seniority, not conceding, fivefoldly diverged; Agni with the Vasu-s, Soma with the Rudra-s, Indra with the Marut-s, Varuṇa with the Āditya-s and Bṛhaspati with the Viśvedeva-s.

They thought: “To the Asura-s, to these foes [of ours], we have succumbed, as we are mutually hostile; whatsoever are our, these, beloved bodies, them we gather together; from these [bodies] he will be lost, who is the first of us to aggress upon/make hostile with/betray one another.”

Therefore, who, among those [who have covenanted] with the Tānūnaptra, first aggresses/makes hostile/betrays, to pain he passes.

The Aitareya-Brāhmaṇa (1.4.7; 1st Pañcikā, 4th Adhyāyaḥ, 7th khaṇḍaḥ) gives a similar account, which we will not translate literally in a full-fledged manner as above but simply note the additional points.

“ते देवा अबिभयुर्। अस्माकं विप्रेमाणम् अन्व् इदम् असुरा आभविष्यन्तीति। ते व्युत्क्रम्यामन्त्रयन्ता अग्निर् वसुभिर् उदक्रामद् ईन्द्रो रुद्रैर् वरुण आदित्यैर् बृहस्पतिर् विश्वैर् देवैस्। ते तथा व्युत्क्रम्यामन्त्रयन्त ते ब्रुवन्।”

“te devā abibhayur| asmākaṃ vipremāṇam anv idam asurā ābhaviṣyantīti| te vyutkramyāmantrayantā agnir vasubhir udakrāmad īndro rudrair varuṇa ādityair bṛhaspatir viśvair devais| te tathā vyutkramyāmantrayanta te bruvan|“

The Devas feared and reflected how due to their disunity, the Asuras are thriving. The Devas go as separate groups in their separate ways to take counsel (four groups as opposed to five in the Taittirīya version). Having taken counsel in their respective parties, they came to a decision.

“हन्त या एव न इमाः प्रियतमास् तन्वस् ता अस्य वरुणस्य राज्ञो गृहे संनिदधामहै; ताभिर् एव नः स न संगछातै यो न एतद् अतिक्रामाद्, य आलुलोभयिषाद्” इति तथेति ते वरुणस्य राज्ञो गृहे तनूः संन्यदधत।

“hanta yā eva na imāḥ priyatamās tanvas tā asya varuṇasya rājño gṛhe saṃnidadhāmahai; tābhir eva naḥ sa na saṃgachātai yo na etad atikrāmād, ya ālulobhayiṣād” iti tatheti te varuṇasya rājño gṛhe tanūḥ saṃnyadadhata|

The Devas thus arrive at a consensus that they should deposit their dearest bodies in the house of King Varuṇa, saying, “With those bodies, he will not be united; who transgresses this, who causes [the Tānūnaptra] to frustrate”. They then deposit their bodies in the house of King Varuṇa.

ते यद् वरुणस्य राज्ञो गृहे तनूः संन्यदधत तत् तानूनप्त्रम् अभवत् तत् तानूनप्त्रस्य तानूनप्त्रत्वं। तस्माद् आहुर् न सतानूनप्त्रिणे द्रोग्धव्यम् इति तस्माद् व् इदम् असुरा नान्वाभवन्ति

te yad varuṇasya rājño gṛhe tanūḥ saṃnyadadhata tat tānūnaptram abhavat tat tānūnaptrasya tānūnaptratvaṃ| tasmād āhur na satānūnaptriṇe drogdhavyam iti tasmād v idam asurā nānvābhavanti

The bodies being deposited in that house is what marks the “Tānūnaptra-ness” of the Tānūnaptra. They say that to the one [who has covenanted] with the Tānūnaptra, no aggression/betrayal is to be allowed. Therefore, the Asuras have perished.

The Aitareya version implies at the end that there is a direct link between the covenant to not betray or aggress upon one another with the defeat of the Asuras. Thus, it is not merely a covenant to not harm one another but effectively a covenant to fight together against anyone who threatens any one of them.

Now we shall see the mādhyandina-śākhā’s Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa (3.4.2; 3rd Kāṇḍa, 4th Adhyāya, 2nd Brāhmaṇa) version, which further adds several distinctive, interesting nuances into the Tānūnaptra lore.

ātithyena vai devā iṣṭvā। tāntsamadavindat te caturdhā vyadravannanyo ‘nyasya śriyā atiṣṭhamānā agnirvasubhiḥ somo rudrairvaruṇa ādityairindro marudbhirbṛhaspatirviśvairdevairityu haika āhurete ha tveva te viśve devā ye te caturdhā vyádravaṃstānvidrutānasurarakṣānyanuvyaveyuḥ॥ 1

“The Devas having sacrificed with the Ātithya (i.e. Ātithyeṣṭi); [among] them strife entered. They fourfoldly separated; not conceding one another’s glory.”

Note: The text then goes on to state the four groups, making a sly reference to the Taittirīya version’s inclusion of a fifth group (Bṛhaspati and the Viśvedeva-s) and pointing out its apparent inconsistency, before ending with a reference to how an Asura-Rakṣa alliance came after and between the Devas, entering the Devas’ ranks. Further note that this version of the text directly links the usual Tānūnaptra lore with the actual ritual context in which the Tānūnaptra is performed (i.e. after the Ātithyeṣṭi).

te ‘viduḥ। pāpīyāṃso vai bhavāmo ‘surarakṣasāni vaí no ‘nuvyavāgurdviṣadbhyo vai radhyāmo hanta saṃjānāmahā ekasya śriyai tiṣṭhāmahā iti ta indrasya śriyā atiṣṭhanta tasmādāhurindraḥ sarvā devatā indraśreṣṭhā devā iti॥ 2

They know: “Wretched verily we have become; the Asura- Rakṣa-s have come between us; to [our] enemies we will succumb, alas! Let us agree; of one [of us]. let us concede the glory!”, thus [saying] they conceded the glory of Indra; therefore, they say, “Indra is all the Devas; with Indra as their eminent one the Devas are.”

tasmādu ha na svā ṛtīyeran। ya eṣām parastarāmiva bhavati sa enānanuvyavaiti te priyaṃ dviṣatāṃ kurvanti dviṣadbhyo radhyanti tasmānna ‘rtīyerantsa yo haivaṃ vidvānna ‘rtīyate ‘priyaṃ dviṣatāṃ karoti na dviṣadbhyo radhyati tasmānna ‘rtīyeta॥ 3

Therefore, let one’s own not quarrel. Whoever [is an enemy] of theirs, [who is] far from them, he enters between them; they (i.e. those who allow discord to foment) do a favourable [deed] for the enemies and, to the enemies, succumb. Therefore, he shall not quarrel. He, who knowing this [truth], does not quarrel, does an unfavourable [deed] for the enemies and does not, to the enemies, succumb. Therefore, let him not quarrel.

te hocuḥ। hantedaṃ tathā karavāmahai yathā na idamāpradivamevājaryamasaditi॥ 4

They (the Devas) said: Hanta! Let us do this, by that which this [agreement] of ours shall become an everlasting friendship.

te devāḥ। juṣṭāstanūḥ priyāṇi dhāmāni sārdhaṃ samavadadire te hocuretena naḥ sa nānāsadetena viṣvaṅyo na etadatikrāmāditi kasyopadraṣṭuriti tanūnaptureva śākvarasyeti yo vā ayam pavate eṣa tanūnapāchākvaraḥ so ‘yam prajānāmupadraṣṭā praviṣṭastāvimau prāṇodānau॥ 5

They, the Deva-s, gathered together their favourite bodies and beloved abodes; they said, “Thereby from us he shall become separate (i.e. no longer one among us), he shall become scattered; who transgresses this [covenant] of ours!” – “Whose, what witness’s, is [this covenant]?” – “[This covenant is] Tanūnapāt’s the strong one’s. Who is that purifies/blows here (i.e. Vāyu), he is the witness of creatures here, entering [creatures]; they (Two) here are the prāṇa and udāna breaths (in and out breaths).

te devāḥ। juṣṭāstanūḥ priyāṇi dhāmāni sārdhaṃ samavadadire ‘thaita ājyānyeva gṛhṇānā juṣṭāstanūḥ priyāṇi dhāmāni sārdhaṃ samavadyante tasmādu ha na sarveṇeva samabhyaveyānnenme juṣṭāstanvaḥ priyāṇi dhāmāni sārdhaṃ samabhyavāyāniti yeno ha samabhyaveyānnāsmai druhyedidaṃ hyāhurna satānunaptriṇe drogdhavyamiti॥ 9

They, the Deva-s, gathered together their favourite bodies and beloved abodes; now, by taking hold of the ghee[-portions] they (the Ṛtvijaḥ/priests) gather together their favourite bodies and beloved abodes; therefore, let him not commit [to the Tānūnaptra covenant] with all and sundry unless the favourite bodies and beloved abodes are commingled. Whosoever he covenants with, to him he shall not betray; verily they say, “To the one [who has covenanted] with the Tānūnaptra, no aggression/betrayal is to be allowed.”

Let us surmise the ten key points of the multiple narratives of the TS, AB and ŚB:

1 The Devas are not able to admit to each other’s pre-eminence and are thus mutually hostile, causing them to go in their separate ways as four or five different parties. They realize that this discord has allowed the Asuras to overpower them or enter their ranks. (TS, AB and ŚB)

2 The Devas first take counsel within their own respective parties to discuss what they ought to do to resolve the conflict. (AB)

3 The Devas conclude that they ought to admit, by consensus, to the pre-eminence of one person among them. (ŚB)

4 The Devas expressly and distinctly agree that the way to remain bound to this decision and make the covenant lasting is only if there is a price to pay for going back on it. (ŚB)

5 The Devas agree that their most cherished bodies/forms and abodes must all be deposited into a common pool (TS, AB and ŚB) and this common pool is entrusted to the guardianship of a leader deity. (AB).

6 The Devas also appoint a witness for the binding agreement, apart from the leader to whom the common pool of assets is entrusted. (ŚB)

7 Whichever Deva betrays the covenant will suffer pain (TS) and will be deprived of all benefits accruing to him by virtue of having had a share in the common pool of assets. This also extends to a forfeiture of his own assets that he had deposited in the common pool in the first place. (TS, AB and ŚB)

8 No betrayal of or hostility towards one another is allowed under the Tānūnaptra covenant. (TS, AB and ŚB).

9 The Asuras perish because no hostility to any one of them is tolerated under the Tānūnaptra, the implication being that hostility to one from outside is deemed as hostility to all. (AB). So, apart from internal hostility, external hostility too is not tolerated.

10 One must be careful about any commitment he makes under the Tānūnaptra because there will be commingling of one’s dearest bodies and abodes with the similar assets of others. Once one commits himself to the Tānūnaptra with another entity, he is bound to them because there is no room for betrayal or going back under the Tānūnaptra. (ŚB)

Let us adopt a metaphor that will help us transmute the above ten points into an insight for how we can understand the philosophical basis of why the unity of Hindudharma makes sense and why, even if it is argued that this unity stands to become more defined in the course of time and is yet incomplete, this unity is not artificial but theologically meaningful.

11 Let the different, organically developing primary religious systems or sects or schools of a land be the Devas.

12 Let counter-religions, which primarily position themselves as opponents of an organically developing religion and are threats to one or more of the primary systems, be the Asuras. The Devas reflect on the need for unity only after the Asuras overpower them. Likewise, the primary religious systems contemplate the case for unity only after being routed by the counter-religions.

13 Let the rituals, liturgies, texts, pantheons, festivals, pilgrimage sites, lore and religious endowments (temples, etc) of the different systems be the contents of the Devas’ common pool of assets, consisting of the Devas’ bodies and abodes.

14 This shared “religious treasury” is deposited under a law that enforces the binding commitment of the parties to one another, in the same way the Devas’ common pool of assets is deposited with or witnessed by a Deva, i.e. Varuṇa in the AB or Vāyu in the ŚB, who punishes falsehood.

15 Among the various systems which have agreed to unite themselves to one another under a binding covenant, there is a chief system, whose pre-eminence and leadership are recognized across all members of the covenant. The chief system’s representative capacity for all other systems is also recognized. Let this chief system be the Deva whose pre-eminence is universally accepted by all other Devas i.e. Indra in the ŚB.

16 Each primary religious system, that is a party to the covenant, undertakes to not only never harm another member of the covenant but also protect one another in event of an external attack from the counter-religions.

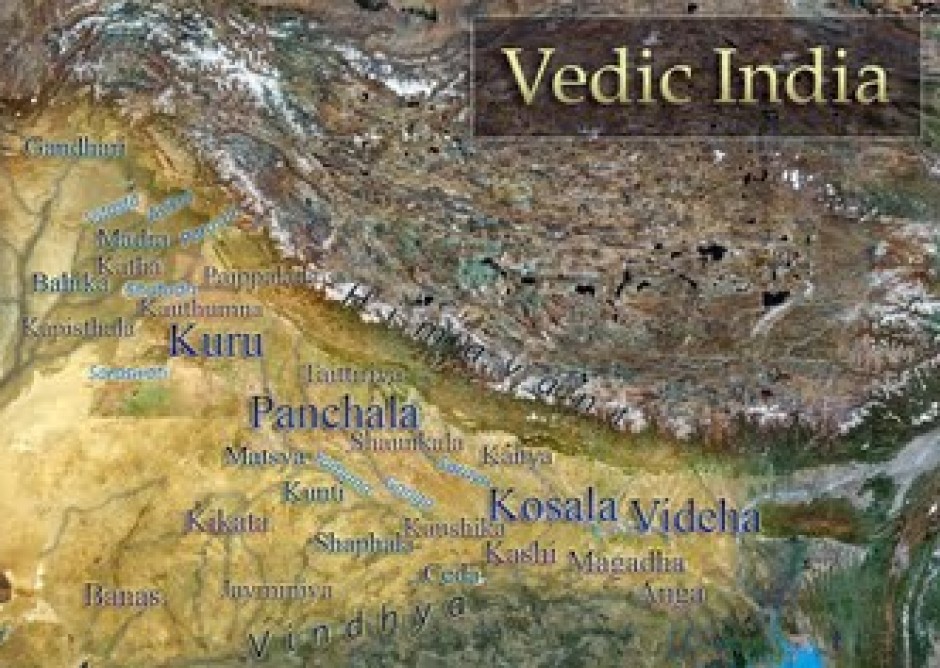

17 The primary religious systems which are parties to the covenant are currently grouped under these following overarching categories: the Vaidika, the Āgamika, Laukika-Paurāṇika, Grāmya and Āṭavika (tribal) religions.

Now, one must add a few nuances to this scenario, which are not available in the Tānūnaptra narratives but nonetheless inspired from them:

18 Just as Indra is chosen by the Devas but we know from the Veda that a Deva may combine with others to form dvandvas (Indrāgni, Indrāvaruṇa, etc), so is the case in the Dharma that the leader system need not remain constant.

Example: The “pure” Vaidika system may have been the leader at some point of time but has coalesced with the Paurāṇika and Āgamika systems for several centuries now, to form a hybrid, that may be argued to be the leader now.

19 Each of the current parties to the covenant of the Dharma may have been the product of a similar covenant between a smaller group of conflicting entities. These smaller-level covenants become subject to the broader covenant but remain binding and enforceable.

Example: We have references from those like Kumārilabhaṭṭa, Jayantabhaṭṭa and even within the Veda, which suggest that the adherents of Vedaśākhā-s may have been hostile to one another. But at some time, the overwhelming majority allowed their fervour for individual Vedaśākhā-s to submit to and make way for the universal supremacy of the unified Veda. This can be seen as a smaller-level covenant. Once this is resolved and the Veda’s pre-eminence qua Veda is established over the individual Vedaśākhā-s, the Veda’s covenant with all other religious systems makes more sense.

20 Sub-systems and/or sects which are born as a result of the binding covenant (i.e born from the “religious treasury”) are automatically admitted into full membership under the covenant and will remain so unless they consciously choose to betray the covenant.

Example: Various systems such as the Mādhva or Vīraśaiva, etc can be said to be the results of complex syntheses of Vaidika, Āgamika and Paurāṇika systems. They are born from the “Tānūnaptra” of the Dharma, one can say. However, if a particular body declares itself as opposed to all other systems (such as when a certain body of Liṅgāyata leaders declared itself separate from Hindudharma and made disparaging statements against other systems), we should not hesitate to exclude them from the “Tānūnaptra”. However, one should note that the actual Liṅgāyata laity on the ground may remain perfectly attached to the Dharma as ever and their Hinduness cannot be negated by the acts of a certain dissident body, which happens to be related to the laity).

21 As a final point, we must note that there can be multiple “Tānūnaptra-s” being realized in the different lands of Bhārata. Can all of these Tānūnaptra-s stand in for a single covenant that is “Hindudharma”?

Example: For instance, there may be a shared understanding, beliefs and practices between the Laukika-bhakti tradition and a tribal religion in Utkala that amounts to a Tānūnaptra there. There may be a similar shared understanding between the particular Āgamika tradition of a temple and a Grāmya tradition surrounding a certain rural deity in Drāviḍadeśa. Can these disparate understandings amount to a single “covenant”?

Our view is that, yes, it is possible though we will elaborate this in a sequel. Tentatively, we suggest that it is a certain uniformity of view across the Laukika and Āgamika traditions that allows them to embrace tribal and village systems into a larger whole along with themselves. An instance of such uniformity lies in the idea that Śiva, Viṣṇu and Devī either manifest themselves as the deities of all peoples or these deities somehow act as the conduits through which Śiva, Viṣṇu and Devī make their power known.

22 Now, we may imagine, thanks to scriptural precedents (Gaṇeśa, Skanda, etc), new Devas take birth and, after an initially unpleasant encounter with the older Devas, join the “Tānūnaptra” (i.e. make peace with the older Devas), though the Tānūnaptra fails to appear in post-vaidika texts such as the Purāṇas. Likewise, can the Hindu Dharma be open to the entry of new members?

Example: The “Tānūnaptras” which materialised in various countries across South-East Asia (and even today) and other regions happened at different points of time & centuries after the “hoarier” Tānūnaptras of the more ancient part of our Dharma’s history.

There is no reason why we cannot continue to enter new Tānūnaptras today. Examples from modern times would include the melding of Folk Chinese/Daoist and Hindu deities in a single ritual space in countries like Singapore. While the creation of such single ritual spaces for two such different traditions is not necessary for a Tānūnaptra, such a space would be one among multiple modes through which a new Tānūnaptra may come into being, apart from Indian Hindus and Chinese polytheists having separate spaces but mutually recognizing each other’s space as sacred & worthy of reverence or even veneration.

Conclusion:

Finally, the Tānūnaptra metaphor also provides sufficient defence against those who complain that historical processes of assimilation and strategic alliances are necessarily markers of the artificiality of the Hindu identity. Why does it provide a defence? Because just like the Devas repeatedly perform sacrifices and may have to renew and update their own Tānūnaptra, our evolving Dharma too is a series of Yajña-s or long Sattra-s, where different pantheons, rituals and sacred spaces meld together, and which requires us to perform the sacred rite of “Tānūnaptra” by committing ourselves to the overarching Hindu identity. Thus, when we commit ourselves to the “Hindu” identity, it is not a mere artificial, survival strategy. It is divine. It is the earthly manifestation of the Tānūnaptra itself. The historical processes of assimilation over thousands of years are embodiments, in real time, of the timeless Tānūnaptra mythical cycle. As such, they are not profane but divine and thus do not render the story of Hindu identity artificial.

We end our essay here and will update it in due time.

A tamil verse on bhṛṅgī-भृङ्गी

A तमिऴ् verse on भृण्गी that I composed in the metro while commuting to a professional event:

உண்டு பிரிவோ உயிருடலிடையே என

उण्डु पिरिवो उयिरुडलिडैये ऎन

வண்டுருக்கொண்டு துளையில் வலஞ்செய்ய

वण्डुरुक्कॊण्डु तुळैयिल् वलञ्जॆय्य

கண்டுமை வெகுண்டு ஊனிழந்த முனிவரை

कण्डुमै वॆगुण्डु ऊनिऴन्द मुनिवरै

கண்டு முக்காலர் முக்காலராய் செய்தாரே

कण्डु मुक्कालर् मुक्कालराय् सॆय्दारे

உண்டு பிரிவோ உயிருடலிடையே என

उण्डु पिरिवो उयिरुडलिडैये ऎन

उण्डु: There is; पिरिवो: पिरिवु means separation; the last syllable transformed to वो makes it a question; thus, “separation?”; उयिरुडलिडैये: उयिर् (life, soul आत्मन् ) + उडल् (body, देह ) + इडैये (between); ऎन: ऎ is the short ‘e’ sound; same as the ‘e’ in the word, “pet” or “sell”. ऎन functions, more or less, in the same way as इति in संस्कृतम्, meaning “thus”; here, as per the context, it is to be rendered as, “thus thinking”;

Translation: “Is there separation between the soul and the body”, thus [thinking]

வண்டுருக்கொண்டு துளையில் வலஞ்செய்ய

वण्डुरुक्कॊण्डु तुळैयिल् वलञ्जॆय्य

वण्डुरुक्कॊण्डु: वण्डु (bee) + उरु (form) + कॊण्डु (कॊ, here the ‘o’ is a short one. The word means getting/having. In this context, it is appropriate to render it as “taking upon”; तुळैयिल्: तुळै (hole) + इल् (A grammatical case-ending denoting the ‘locative case’-i.e. “in the”); वलञ्जॆय्य: वलम् (circumbulation) + चॆय्य (the ‘che’ here has a short ‘e’, like the word for the musical instrument, ‘cello’; चॆय्य means, doing)

Translation: Taking upon a bee-form, and in the hole circumbulating;

கண்டுமை வெகுண்டு ஊனிழந்த முனிவரை

कण्डुमै वॆगुण्डु ऊनिऴन्द मुनिवरै

कण्डुमै: This should be split as कण्ड + उमै (கண்ட + உமை); कण्ड (saw/seeing) + उमै (उमादेवी); वॆगुण्डु: (वॆ has a short ‘e’, just like the ve in velvet; the word means, “got angry”; but it must be read with the rest of the line; the last word of the 3rd line is the object of the entire verse); ऊनिऴन्द: ऊन् (body/flesh) + इऴन्द (lost) मुनिवरै (that मुनि-)

Translation: The मुनि who lost his flesh by the wrath of उमा seeing [him]

Translation in context: The मुनि who lost his flesh by the wrath of उमा seeing the मुनि who, thinking, “Can there be separation between soul and body?”, take upon the form of a bee to bore a hole through अर्धनारीश्वर and circumbulate only the right half that is शिव.

கண்டு முக்காலர் முக்காலராய் செய்தாரே

कण्डु मुक्कालर् मुक्कालराय् सॆय्दारे

कण्डु: Saw/seeing; मुक्कालर्: मु (three) + कालर् (one who abides in time); thus, one who abides in all three times; मुक्कालराय्: मु (three) + कालर् (legged one; in तमिऴ्, काल् means leg) + आय् (a grammatical ending to indicate a transformation); सॆय्दारे: सॆय्दार् (did/made) + ए (an emphatic particle used to stress).

Translation: Seeing [that मुनि], the [great god,] one [who abides] in all three times, made him (the मुनि) a three-legged one.

Overall Translation: “Can there be separation between soul and body?”, thus thinking, taking upon the form of a bee to bore a hole through अर्धनारीश्वर and circumbulating only the right half that is शिव; the मुनि lost his flesh as उमा saw him do that; seeing the मुनि thus, he, the great god abiding forever in all three times, made him three-legged.

The poem above compactly encapsulates the story of भृङ्गी, a fanatical भक्त of महादेव, the curse on him by उमा to be emptied of his flesh & the subsequent blessing by शिव with a 3rd leg to support himself, and, in fact, become a teacher of dance! Here, I tried to redeem भृङ्गी by giving his act a deeper meaning (रहस्यार्थ). He did not mean to slight the देवी by refusing to worship her. So, what was the motive?

He (in my poetic license; may हरः & अम्बा be pleased) thought that since she is inseparable from him as a body is from the soul, why should he violate this truth by worshiping her separately? In the सिद्धान्त-शैव system, the relationship of शिव and शक्ति is analogous to that of the soul and body, respectively. And thus, to instruct him on the importance of honouring शिव $ देवी together but distinctly, she empties his body of all flesh & substance, in line with his understanding that honouring the self/soul (शिव) negates the need for honouring the body (शक्ति) separately.

Of course, due to her compassion for an exalted भक्त of शिव , she stops short of making him completely disembodied. Nevertheless, with his body essentially emptied, भृङ्गी has no support to stand upon. However, शिव being the शक्तिमान्, while not undoing the effect of शक्ति’s words, grants him a divine 3rd leg, which supports him. Not only does it support him; but with this 3rd leg alone, भृङ्गी dances together with the three-eyed god; just like the three-eyed god. For it is शिव, who has शक्ति, with all her forms and names, in his eternal lordship as the शक्तिमान्, and bestows grace upon his भक्त-s as he pleases, as the श्रीमन्-मृगेन्द्रागम tells us.

sadāśiva-stuti:

A modest attempt:

ककपालपालकपाल।

कलपाककालपाकाकाल॥

कालपापकलापपाकपालक।

कालकलकलाकलाकालाकलपाक॥

kakapālapālakapāla।

kalapākakālapākākāla॥

kālapāpakalāpapākapālaka।

kālakalakalākalākālākalapāka॥

Lyrical/Free-Flowing Translation (for easier comprehension)

You with brahmā’s Skull as Begging Bowl; the Protector of brahmā!

You, the timeless one, who cooks Time himself, who cooks the souls bound by limited agency (and other limiting factors)!

You who protects that which cooks/burns up the the dark mass of sins!

You who perfects the two classes of souls who are no longer bound by limited agency : One which becomes unbound only at the uproarious end of time during dissolution & One which becomes unbound without such time-bound conditions.

Translation with word by word breakdown:

क-कपाल-पाल-क-पाल

ka-kapāla-pāla-ka-pāla

You, the protector (pāla) of brahmadeva (ka) who has the skull of brahmadeva (kakapāla) as his begging bowl (pāla)!

One could interpret this as either: a. That śiva has graced brahmā by that act of removing the fifth head; or b. one who protects brahmā even as he holds the skull of the fifth head. A symbolic meaning of the removal of the 5th head is given by tryambakaśambhu in his kiranāgama-śisuhitavṛtti as the awakening of the kuṭilā-śakti in the heart region, which is seen as the abode of brahmā in the kāmikāgama.

कल-पाक-काल-पाक-अकाल

kala-pāka-kāla-pāka-akāla

This verse, for convenience, can be rewritten as two distinct parts, with the term, “kāla” duplicated.

You, the timeless one (akāla) who cooks the time (kāla-pāka) itself, who cooks the kala-s (kalapāka), that is the sakala class of jīvātmas, ones covered with kalādi (kalā/कला, etc) bandha-s i.e. limited souls like us!

kala-pāka-kālaḥ—Here, kālaḥ/time is the subject of the sentence; the kāla which “cooks” the souls immersed in bondage due to a sense of limited agency (the sakala-s, the kala-s/कला:, who are bound by kalā).

kāla-pāka-akāla—Here, kāla/time becomes the object, with akāla becoming the subject in the vocative case (sambodhana-vibhakti). You, the timeless śiva, who is the very destroyer of time (I.e. destroys time)!

Please do not confuse kāla/काल (time) with kalā/कला, which is a unique concept in śaiva philosophy (particularly well-developed in the siddhānta flavour of śaivam), which, to put it simply without complicating excessively, refers to the idea of “limited agency” that we all have: “I am a particular individual who is the agent of these actions and the enjoyer/sufferer of their fruits”. Those who keep suffering due to the effect of kalā; they are sakala-s, like us, whom I have referred to here as kala-s. These souls keep getting “cooked” by time in the fires of repeated birth and death.

Do note that the term, “pāka”, occurring in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th lines, is used in different senses.

2nd line: Cooked in the fire of repeated saṃsāra

3rd line: Refers to the cooking/burning off of sins by the purifying śivajñāna (Wisdom of the siddhānta)

4th line: Refers to the cooking (spiritual ripening/perfection/maturation) of two categories of souls, who are above us, the ordinary, sakala category of souls

काल-पाप-कलाप-पाक-पालक

kāla-pāpa-kalāpa-pāka-pālaka

You, the protector (pālaka) who cooks the bundle (kalāpa) of dark sins (kāla-pāpa). Or alternatively, it could mean the one who protects the śivajñāna (i.e. the siddhānta), which cooks the bundle of dark sins!

कालकलकलाकलाकालाकलपाक

kāla-kalakala-akala-akāla-akala-pāka

The ones who become akala-s only during pralayakāla, which is the uproarious moment of kāla (kāla-kalakala-akala), that is the pralaya-akala-s (pralayākala class of jīvātmas).

Those who are akala-s outside the boundaries of time (akala-akāla); that is, the vijñānākala-s (vijñāna-akala-s); you, the one who causes their mala to ripen, that is, malaparipAka; literally and figuratively, you, the one who cooks both of them to spiritual perfection (pāka)!

Or simply put: You, who “cooks” (i.e. perfects or causes to mature/ripen) the pralayākala and vijñānākala categories of souls!

A gurupūjā Dedication to jñānasambandha nāyanār svāmi

With the moon passing through the mūla (मूल) nakṣatra in the tamiḻ month of vaikāsi (equivalent of saṃskṛta vaiśākha (वैशाख), today happens to be the glorious day of gurupūjā for śrī jñānasambandha nāyanār svāmi (श्री ज्ञानसम्बन्ध नायनार् स्वामि). In śaiva siddhānta, the day where the great bhakta leaves this world for śiva is commemorated as gurupūjā. Among the sixty-three nāyanār-s (नायनार्-s) whose individual lives are richly and ornately memorialized in classical tamiḻ in the periyapurāṇam, the 12th and final book of the tamiḻ śaiva canon, the life and legacy of tiru-jñānasambandhar (तिरु-ज्ञानसम्बन्धर् – the -r at the end is to indicate respect in tamizh; the tiru/तिरु is tamiḻ for śrī) indeed stands out.

The author of the periyapurāṇam, śrī cēkkiḻār (चेक्किऴार्) gives us the life of jñānasambandhar in the 28th chapter of the book. What was the purpose of the birth of jñānasambandhar?

வேதநெறி தழைத் தோங்க vēdaneṟi taḻait tōṅka वेदनॆऱि तऴैत् तोङ्क

மிகுசைவத் துறைவிளங்கப் mikucaivat tuṟaiviḷaṅkap मिकुचैवत् तुऱैविळङ्कप्

பூதபரம்பரை பொலியப் bhūtaparamparai poliyap भूतपरम्परै पॊलियप्

புனிதவாய் மலர்ந்தழுத puṉitavāy malarntaḻuta पुऩितवाय् मलर्न्तऴुत

சீதவள வயற்புகலித் sītavaḷa vayaṟpukalit सीतवळ वयऱ्पुकलित्

திருஞான சம்பந்தர் tiruñāṉacampantar तिरुञाऩचम्पन्तर्

பாதமலர் தலைக்கொண்டு pādamalar talaikkoṇṭu पादमलर् तलैक्कॊण्टु

திருத்தொண்டு பரவுவாம் tiruttoṇṭu paravuvām तिरुत्तॊण्टु परवुवाम्

Audio of Vocal Rendition by śrī saṟgurunātha: http://thevaaram.org/isai/122/12280001.mp3 (Click link)

The meaning:

For the dharma of the veda to thrive and prosper,

For the great śaiva path to shine,

For the lineages of living beings to flourish,

The one who cried with his flowery mouth;

[Hailing from the city] Of pukali of cool and fecund fields,

[This] tiru-jñānasambandhar;

His feet-flower; bearing them on our head

His divine service, we shall sing of!

What is this crying that the poet speaks of in the introductory verse? It is said that it is for sake of the veda, śaiva-dharma and living beings, that he cried! Why so? At the tender age of about three, on one fine morning, jñānasambandhar, born in the kauṇḍinya-gotra (कौण्डिन्य-गोत्र) to parents śivapādahṛdaya and bhagavatī (शिवपादहृदय and भगवती), followed his father to the brahmapurīśvara (ब्रह्मपुरीश्वर) temple of his birth-city of sīrkāḻi (सीर्काऴि), also known as pukali (पुकलि). When his father, after performing the morning ablutions, immersed in the waters of the temple pond to recite the sin-destroying aghamarṣaṇa-sūktam (अघमर्षण-सूक्तम्), the divine infant cried for his father had been long away from him. Looking at the grand gopura in front of him, remembering his real, non-earthly parents, he cried, “ammē appā” (अम्मे अप्पा – “Mother, Father!”).

And then, the divine parents manifested before them and the mother of the world nursed him with her divine milk, endowing him with the knowledge of the veda-s four and the āgama-s twenty-eight. His work on earth began with this magnificent hymn:

தோடுடைய செவியன் விடையேறி யோர் தூவெண்மதிசூடிக்

तोडुडैय चॆवियऩ् विडैयेऱि योर् तूवॆण्मतिचूडिक्

tōḍuḍaiya ceviyaṉ viḍaiyēṟi yōr tūveṇmaticūḍik

காடுடைய சுடலைப் பொடிபூசியென் உள்ளங்கவர்கள்வன்

काडुडैय चुडलैप् पॊदिपूसियॆऩ् उळ्ळङ्कवर्कळ्वऩ्

kāḍuḍaiya cuḍalaip podipūsiyeṉ uḷḷaṅkavarkaḷvaṉ

ஏடுடைய மலரான் முனை நாட் பணிந்தேத்த வருள் செய்த

एडुडैय मलराऩ् मुऩै नाट् पणिन्तेत्त वरुळ् चॆय्त

ēḍuḍaiya malarāṉ muṉai nāṭ paṇintētta varuḷ ceyta

பீடுடைய பிரமாபுர மேவிய பெம்மானிவனன்றே.

पीडुडैय पिरमापुर मेविय पॆम्माऩिवऩऩ्ऱे.

pīḍuḍaiya piramāpura mēviya pemmāṉivaṉaṉṟē.

Audio of vocal rendition (two renditions): http://thevaaram.org/isai/01/1001001.mp3

Translation: Mounting the bull, the one whose ears are adorned with the [female] ear-ring; adorning a pure, white moon, smearing the charnel-ash of the [cremation-] forest, the thief who thieves [away] my mind! Is he not that great lord [whom] the petaled-lotus-[seated]-one (brahma) had, in days of yore, worshiped, [who] did grace [to brahma]; [who] dwells in glory-possessing brahmāpura?

One could read the hidden import of this beautiful opening verse here: https://twitter.com/drAviDastotra/status/1095807012514996224

The greatness of jñānasambandhar is best illustrated by the words of those who are known to be equally exalted as him: The two other authors of the devāram (देवारम्): śrī vāgīśa (श्री वागीश), also known as tirunāvukkarasar (तिरुनावुक्करसर्), the king of speech, who was his contemporary and śrī sundaramūrti (श्री सुन्दरमूर्ति), who postdates both of them and is the first person to give us a poetic list of all the nāyanār-s (both individuals and groups).

When jñānasambandhar, after many of his travels and glorious deeds of holding the flag of dharma high against the nāstika-s who had abused the veda and śiva very much, went to the city of tiruppūnturutti (तिरुप्पून्तुरुत्ति) to meet tirunāvukkarasar who was of already advanced age, the latter, having heard of the arrival of the divine child, joined the crowd of devotees to bear the pearly palanquin of the prince of the city of pukali. At that time, jñānasambandhar felt in his divine buddhi (intellect) that something was amiss. I will let the divinely inspired cēkkiḻār to tell us the tale and post the translation, for convenience, as given by T. N. Ramachandran (which I find reliable/accurate for these three verses)

Verse 934: Audio: http://thevaaram.org/isai/123/12280934.mp3

வந்தணைந்த வாகீசர் vantaṇainta vākīcar वन्तणैन्त वाकीचर्

வண்புகலி வாழ்வேந்தர் vaṇpukali vāḻvēntar वण्पुकलि वाऴ्वेन्तर्

சந்தமணித் திருமுத்தின் cantamaṇit tirumuttiṉ चन्तमणित् तिरुमुत्तिऩ्

சிவிகையினைத் தாங்கியே civikaiyiṉait tāṅkiyē चिविकैयिऩैत् ताङ्किये

சிந்தைகளிப் புறவருவார் cintaikaḷip puṟavaruvār चिन्तैकळिप् पुऱवरुवार्

திருஞான சம்பந்தர் tiruñāṉa campantar तिरुञाऩ चम्पन्तर्

புந்தியினில் வேறொன்று puntiyiṉil vēṟoṉṟu पुन्तियिऩिल् वेऱॊऩ्ऱु

நிகழ்ந்திடமுன் புகல்கின்றார் nikaḻntiṭamuṉ pukalkiṉṟār निकऴ्न्तिटमुऩ् पुकल्किऩ्ऱार्

Verse 935: Audio: http://thevaaram.org/isai/123/12280935.mp3

அப்பர்தாம் எங்குற்றார் appartām eṅkuṟṟār अप्पर्ताम् ऎङ्कुऱ्ऱार्

இப்பொழுதென் றருள்செய்யச் ippoḻuteṉ ṟaruḷceyyac इप्पॊऴुतॆऩ् ऱरुळ्चॆय्यच्

செப்பரிய புகழ்த்திருநா ceppariya pukaḻttirunā चॆप्परिय पुकऴ्त्तिरुना

வுக்கரசர் செப்புவார் vukkaracar ceppuvār वुक्करचर् चॆप्पुवार्

ஒப்பரிய தவஞ்செய்தேன் oppariya tavañceytēṉ ऒप्परिय तवञ्चॆय्तेऩ्

ஆதலினால் உம்மடிகள் ātaliṉāl ummaṭikaḷ आतलिऩाल् उम्मटिकळ्

இப்பொழுது தாங்கிவரப் ippoḻutu tāṅkivarap इप्पॊऴुतु ताङ्किवरप्

பெற்றுய்ந்தேன் யான்என்றார் peṟṟuyntēṉ yāṉeṉṟār पॆऱ्ऱुय्न्तेऩ् याऩ्ऎऩ्ऱार्

Verse 936: http://thevaaram.org/isai/123/12280936.mp3

அவ்வார்த்தை கேட்டஞ்சி avvārttai kēṭṭañci अव्वार्त्तै केट्टञ्चि

அவனியின்மேல் இழிந்தருளி avaṉiyiṉmēl iḻintaruḷi अवऩियिऩ्मेल् इऴिन्तरुळि

இவ்வாறு செய்தருளிற் ivvāṟu ceytaruḷiṟ इव्वाऱु चॆय्तरुळिऱ्

றென்னாம்என் றிறைஞ்சுதலும் ṟeṉṉāmeṉ ṟiṟaiñcutalum ऱॆऩ्ऩाम्ऎऩ् ऱिऱैञ्चुतलुम्

செவ்வாறு மொழிநாவர் cevvāṟu moḻināvar चॆव्वाऱु मॊऴिनावर्

திருஞான சம்பந்தர்க் tiruñāṉa campantark तिरुञाऩ चम्पन्तर्क्

கெவ்வாறு செயத்தகுவ kevvāṟu ceyattakuva कॆव्वाऱु चॆयत्तकुव

தென்றெதிரே இறைஞ்சினார் teṉṟetirē iṟaiñciṉār तॆऩ्ऱॆतिरे इऱैञ्चिऩार्

Translation:

Such is the impeccable greatness of jñānasambandhar. We could continue narrating much much more about the glory of the child-prince of pukali. But we will end it today with one of his greatest verses. When the jaina-s of Madurai, having failed in their plot to assassinate the divine child and having failed to keep their parchment from burning in the flames (which dared not harm the writing of the glorious prince of pukali, called for their parchments to be placed in the ferocious waters of river vaigai, the parchment of the nāstika-s was scattered into oblivion by the ferocious current of vaigai, while the one by sambandhar marched against the current and established the eternal truth of the veda, that is śivadharma (शिवधर्म). He wrote ten verses on those blessed leaves. And this is the opening verse of that hymn he set against the vaigai current:

வாழ்க அந்தணர் வானவ ரானினம் vāḻka antaṇar vāṉava rāṉiṉam वाऴ्क अन्तणर् वाऩव राऩिऩम्

வீழ்க தண்புனல் வேந்தனு மோங்குக vīḻka taṇpuṉal vēntaṉu mōṅkuka वीऴ्क तण्पुऩल् वेन्तऩु मोङ्कुक

ஆழ்க தீயதெல் லாமர னாமமே āḻka tīyatel lāmara ṉāmamē आऴ्क तीयतॆल् लामर ऩाममे

சூழ்க வையக முந்துயர் தீர்கவே cūḻka vaiyaka muntuyar tīrkavē चूऴ्क वैयक मुन्तुयर् तीर्कवे

Let the brāhmaṇas, sky-dwelling devas and the race of cows live long!

Let cool water (rain) pour!

Let the king become exalted!

Let all the evils be subjugated!

Let the name of hara encompass all!

Let the world be free from sufferings!

May the blessings of jñānasambandhar, who was praised as skanda himself, be showered upon bhārata at this significant time!

Image Source: https://shaivam.org/gallery/image/devotees/sambandar.png

किरणागमान्तर्गतशिवस्तोत्रम् – kiraṇāgamāntargataśivastotram – A saiddhāntika stotra from the kiraṇāgama by garuḍa to śrīkaṇṭha-rudra

In the saiddhāntika śaiva system, there are twenty-eight mūlāgama-s (primary āgama-s), each of which is traditionally supposed to be complete with four distinct sections:

- vidyāpāda

- yogapāda

- kriyāpāda

- caryāpāda

The kiraṇāgama (also known as the kiraṇamahātantra) begins with the vidyāpāda, the section/pāda of an āgama text which covers the “vidyā” portion of an āgama, covering the matters of how the various āgama-s were revealed and to whom they were revealed, the doctrine of tattva-s (the fundamental principles which constitute all of existence; in the saiddhāntika and bhairava streams of mantramārga śaivam, there are 36 tattva-s) and other such philosophical matters. The vidyāpāda of the kiraṇāgama opens with this verse by garuḍa:

कैलासशिखरासीनं सोमं सोमार्धशेखरम्।

हरं दृष्ट्वाब्रवीतार्क्ष्यः स्तुतिपूर्वमिदं वचः

kailāsaśikharāsīnaṃ somaṃ somārdhaśekharam|

haraṃ dṛṣṭvābravīttārkṣyaḥ stutipūrvamidaṃ vacaḥ

[The one] seated on a summit of mount kailāsa, the soma (Here, it figuratively means, “one with umā”), the one crowned with the half-moon, the hara (Figuratively, the one who removes the bonds of the soul); preceded by a stuti, having seen him, tārkṣya (garuḍa-deva) says these words.

Here, the great saiddhāntika commentator of kāśmīradeśa, the great lion of siddhānta śaivam, mahākaṇṭha kaṇṭhīrava śrī bhaṭṭa rāmakaṇṭha (hereafter, rāmakaṇṭha), takes the pains to explain the order in which the opening events of the text takes place:

- Firstly, the stuti of garuḍa takes place: This beautiful stuti is given in śloka-s 2 to 9 of the first chapter of the āgama.

- Secondly, having uttered the words of praise, garuḍa obtains the sight of śrīkaṇṭha-rudra.

- Thirdly and finally, having now seen his guru, śrīkaṇṭha-rudra, garuḍa then utters the words (the question in śloka 10 of the text), opening the sacred dialogue between master and disciple.

We will see the actual commentary in detail in a subsequent post, or a subsequent edit of this very post. Now, we will see this stuti of 8 śloka-s, where the word, “jaya” appears a total of sixteen times.

जयान्धकपृथुस्कन्धबन्धभेदविचक्षण।

jayāndhakapṛthuskandhabandhabhedavicakṣaṇa

Victory, oh one skilled in splitting the knot of the broad shoulders of andhaka!

जय प्रवरवीरेशसंरुद्धपुरदाहक॥

jaya pravaravīreśasaṃruddhapuradāhaka ॥

Victory, oh burner of the [threefold] city, held/concealed by those most distinguished among the lords of the heroes/vīra-s (the three tripurāsura-s)

जयाखिलसुरेशानशिरश्छेदभयानक।

jayākhilasureśānaśiraśchedabhayānaka ।

Victory, oh fearsome one, [who] lopped off a head of the lord of all the deva-s (brahma)!

जय प्रथितसामर्थ्यमन्मथस्थितिनाशन॥

jaya prathitasāmarthyamanmathasthitināśana ॥

Victory, oh one who is the very destruction of that manmatha (kāmadeva), whose skill/ability [to induce passions] is well-renowned/widely-spread.

जयाच्युततनुध्वंसकालकूटबलापह।

jayācyutatanudhvaṃsakālakūṭabalāpaha ।

Victory, oh one who removes the power of the kālakūṭa [poison], which ruined the body of acyuta!

जयावर्तमहाटोपसरिद्वेगविधारण॥

jayāvartamahāṭopasaridvegavidhāraṇa ॥

Victory, oh the bearer (vidhāraṇa) of the force/speed (vega) of the river (sarit), which is greatly proud/haughty (maha+āṭopa) with its windings/curves (āvarta)!

जय दारुवनोद्यानमुनिपत्नीविमोहक।

jaya dāruvanodyānamunipatnīvimohaka ।

Victory, oh deluder of the sages as well as their wives in the dāruvana garden-grove!

जय नृत्तमहारम्भक्रीडाविक्षोभदारुण॥

jaya nṛttamahārambhakrīḍāvikṣobhadāruṇa ॥

Victory, oh who dreads [the world] with shaking, due to the great exertion/effort of the play of his dance!

जयोग्ररूपसंरम्भत्रासितत्रिदशासुर।

jayograrūpasaṃrambhatrāsitatridaśāsura ।

Victory, oh one who, assuming the fierce form, terrified the thirty (tridaśa, a synonym for deva) and the asuras (Basically, the devāsura-s)!

जयक्रूरजनेन्द्रास्यदर्शितासृक्सुनिर्झर॥

jayakrūrajanendrāsyadarśitāsṛksunirjhara ॥

Victory, one who, in the mouth of the lord of the cruel folks, showed a stream of blood!

Note: Due to the sheer strange wording of the verse, this is my favorite part of the whole stuti. While, on a surface reading, commentators have identified this line to pertain to the episode, where śiva humbles rāvaṇa by pressing down the mountain on his heads, one of the commentators, the venerable śrī tryambakaśambhu, gives a rich and beautiful inner meaning of this line, which we will see in a subsequent post or subsequent edit of this post.

जय वीरपरिस्पन्ददक्षयज्ञविनाशन।

jaya vīraparispandadakṣayajñavināśana ।

Victory, oh who is (or caused) the destruction of dakṣa’s sacrifice by stirring up (parispanda) the hero/vīra (that is, vīrabhadra)

जयाद्भुतमहालिङ्गसंस्थानबलगर्वित॥

jayādbhutamahāliṅgasaṃsthānabalagarvita ॥

Victory, one who took pride in that form (saṃsthāna) of the liṅga, wondrous (adbhuta) and great (maha)!

जय श्वेतनिमित्तोग्रमृत्युदेहनिपातन।

jaya śvetanimittogramṛtyudehanipātana ।

Victory, oh one who, for the sake of śveta-muni, felled the body of fierce death (ugramṛtyu)!

जयाशेषसुखावासकाममोहितशैलज॥

jayāśeṣasukhāvāsakāmamohitaśailaja ॥

Victory, who has infatuated/bewitched the daughter of the mountain (śailaja; that is umā) with desire (kāma); [this kāma] which is the abode (vāsa) of the totality (aśeṣa) of pleasures (sukhā)!

जयोपमन्युसन्तापमोहजालतमोहर।

jayopamanyusantāpamohajālatamohara ।

Victory, oh one who removed the great heat/torture (santāpa) of upamanyu and the darkness (tamas) of the web (jāla) of delusion (moha)!

जयपातालमूलोर्ध्वलोकालोकप्रदाहक॥

jayapātālamūlordhvalokālokapradāhaka ॥

Victory, oh one who burns (pradāhaka) [these] worlds (loka-s) and the aloka-s (the non-human worlds ranging from those of piśāca-s to brahmadeva) from above (ūrdhva) the root (mūla) of the pātāla-s!

Note: In the siddhānta cosmology, below the pātāla-s are the naraka-s, which are directly above the world of kālāgni-rudra. At the time of absolute destruction, kālāgnirudra engulfs all the worlds above it.

We have thus ended the simple translation of the stuti. We hope to delve, as soon as possible, deep into the symbolic meanings and the classical commentaries on the stuti by the boundless grace of sadāśiva.

May the sixteen loud and thunderous jaya-s of the stuti shake the skulls of those who mock śiva and his āgama-s; may the deva praised by the four vedas and twenty-eight āgama-s protect the student of the hymn!

mahāśivarātri: Attempt at a saṃskṛta verse on śiva

This is just an attempt by someone with zero background in saMskRta poetry. There is no metre here per se. But may these 4 lines of 28 syllables each be an offering to the god who gave the 28 siddhAnta Agama-s as the essence of the 4 veda-s for mahāśivarātri

यश् चिदम्बरपतिः-स्वरूपविरहकृत-कलङ्कसूदक-सुकार्येण शोभितः

यो निध्यम्बरीपति-सुरूपवराहकृत-सपङ्कजोदक-विहारेण क्षोभितः

यो विद्याम्बरपतिस्-सूकरसुरदधृत-शिवाङ्कमोदको कुमारं लेखयति

सो विध्याम्बरपतिस्-सूरतसुकरभृत-सटङ्कबोधको विद्यां मां प्रापयति

yaś cidambarapatiḥ svarūpavirahakara-kalaṅkasūdaka-sukāryeṇa śobhitaḥ

yo nidhyambarīpati-surūpavarāhakṛta-sapaṅkajodaka-vihāreṇa kṣobhitaḥ

yo vidyāmbarapatis-sūkarasuradadhṛta-śivāṅkamodako kumāraṃ lekhayati

so vidhyāmbarapatis-sūratasukarabhṛta-saṭaṅkabodhako vidyāṃ māṃ prāpayati

Notes:

a. यश् चिदम्बरपतिः-स्वरूपविरहकृत-कलङ्कसूदक-सुकार्येण शोभितः

yaś cidambarapatiḥ svarūpavirahakara-kalaṅkasūdaka-sukāryeṇa śobhitaḥ

He (yaH) who is the lord of the cidambara (City or inner space of heart where brahman dwells), the one who is adorned (shobhitaH) by the good actions (sukAryeNa) of the crushing (sUdaka) of the stain (kalaGka) which causes (kara) by the seperation (viraha) from the svarUpa

This refers to the siddhAnta doctrine that the primal impurity of ANava (atomism) or mUla-mala (thus, the filth/stain) falsely makes one think that he is a finite, embodied soul (atom) when he is reality is as expansive and blissful as shiva. Shiva removes this filth by means of dIkSA and anugraha (Grace). He is ornamented by the numerous initiations and other acts of grace, where he has graced souls with the removal of mala.

b. यो निध्यम्बरीपति-सुरूपवराहकृत-सपङ्कजोदक-विहारेण क्षोभितः

yo nidhyambarīpati-surūpavarāhakṛta-sapaṅkajodaka-vihāreṇa kṣobhitaḥ

He who is agitated (kSobhitaH) by the [erotic] play (vihAreNa) in the lotus-endowed waters (sapaGkajodaka) by varAha of good form (surUpavarAha), the lord (pati) of the one who has the oceans (nidhi) as her garments nidhyambarI–earth)

The idea for this is from shrI sambandhar’s & appar’s old tamizh poems where he refers to varAha’s tusk on the neck of shiva as an ornament. varAha after finishing his work is imagined in some purANas as indulging in erotic sport with bhUdevI. That play has been imagined as a play in the muddy (paGka) lotus-filled waters….

shiva is apparently upset with that play which causes the cosmos to tremble and after causing him to leave that body & go back to his blissful & peaceful station in vaikuNTha, keeps varAha’s tusk as keepsake. But as we will see in line 3, the tusk comes handy.

Also, the word paGkaja has been chosen for lotus as mud invokes shrI varAha association very well and sapaGkajodaka rhymes with previous line’s kalaGkasUdaka & subsequent shivAgkamodaka & saTaGkabodhaka.

c. यो विद्याम्बरपतिस्-सूकरसुरदधृत-शिवाङ्कमोदको कुमारं लेखयति

yo vidyāmbarapatis-sūkarasuradadhṛta-śivāṅkamodako kumāraṃ lekhayati

He who is the lord (patiH) with vidyA (knowledge) as his garments (vidyAmbara), who makes write (lekhayati) kumAra, who, holding (dhRta) the good tusk (su-rada) of the boar (sUkara), delights (modaka) the lap of shivA (devI) (shivAGka)

The basic premise for this whole poem was this imagery of baby skanda doing akSarAbhyAsam with the tusk of his uncle that shiva kept as souvenir when helping him get out of the avatAra and go back to vaikuNTha. Since he is too young to do it, shiva makes him write with that tusk.

d. सो विध्याम्बरपतिस्-सूरतसुकरभृत-सटङ्कबोधको विद्यां मां प्रापयति

so vidhyāmbarapatis-sūratasukarabhṛta-saṭaṅkabodhako vidyāṃ māṃ prāpayati

That one; he, the lord of the cloth to be pierced (vidhya+ambara; vidhya: to be pierced), the one who supports/carries (bhRta) the good-natured/compassionate (sUrata) ones of good actions (sukara); the teacher (bodhakaH) endowed with the axe (saTaGka; referring to the iconographic axe); he (the one who is all these things described in these four lines) causes me (mAm) to attain (prApayati) knowledge (vidyA).

The cloth to be pierced is the tiras of shaiva siddhAnta; the tirodhana shakti of shiva that veils our consciousness and limits our self-awareness. It is a cloth/curtain that is to be pierced (vidhya) as that is the main function of sadAshiva–to pierce through the veil and free us…..Since shiva/sadAshiva is the lord of this tiras/curtain, the lord of the tirodhana shakti; he is called vidhyAmbarapati.

He carries and sustains the great sages, gods and bhaktas who have pleased him with good acts. He causes me to attain knowledge.

The author of this poem thanks @yaajushi bhagini for her kind assistance and constructive criticisms, and @rkedar1 and @pinakasena for their feedback on the poem.

A short discussion on pertinent issues presented by the sabarimalA matter

It’s often argued that restrictive rules, in terms of temple entry or offering worship at one, impinge upon the “right to participate in religion” of those who are thus restricted. This stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of participation as intrinsically a positive act.

What do I mean by “positive act”? Most of us see would see participation as actually (and thus, positively) doing acts one generally does in a religious setting: such as entering a temple or performing a particular ritual.

However, this is not a realistic understanding of our dharma or any religion for that matter. When you participate in a religion, you do so, not only by doing what you are obligated to do, or doing something optional but allowed for you, but also by not doing what is prohibited.

You participate in the dharma when you abstain from meat on vrata/upavAsa days or enter a temple after removing footwear. That “negative acts” or abstentions were seen as participation is clear when one reads our texts. Let me elaborate.

Negative obligations are a core & critical component of participation. This is why “yama” (restraint) is one of the eight components of aSTANGga yoga. This is why various types of vrata-s are part of popular dharma as encapsulated in the purANa-s & other sources.

This is why yAmuNAcArya, the great shrIvaiSNava AcArya, holds in his AgamaprAmANya that, in truth, nobody is fully forbidden from “shrautam”. Why, because the shruti has general, restrictive injunctions like “Don’t injure creatures”, etc which every human is qualified to follow.

Similarly, when a woman, identified as having reproductive capabilities (for practical purposes, identified as a 10-50 age group), accepts the restriction pertaining to sabarimala with devotion, she is fully participating in the religion, in the worship of the deity.

This “negative” participation is, in no way, less profound and meaningful than the direct, “positive” participation of the men and women of the allowed age groups. One such example of such a participation can be seen in this wonderful music video here: https://t.co/8xDrA2wIHM

The core point at the centre of all this is that within any system, its followers truly participate only be adhering to both the positive obligations and negative injunctions (prohibitions) which define the very unique essence and identity of that system.

And this is not uniquely applicable to Hindu sects but will apply to any belief-practice system defined as a religion. You cannot be said to participate in a religion if you are not participating in the dietary, sexual or other restrictions laid down in that religion.

At this point, one may raise the argument that the restrictions in the case of sabarimala are not left to the conscience of the worshipper but enforced and thus, this would impinge upon the freedom of the individual worshipper to practice the religion as he or she sees fit.

The only real & truly honest response to this argument is that the temple is essentially the residence of the deity who is also the owner of the temple & is entitled to an absolute enjoyment of this property, as amply indicated by terms such as devasvam, devagRha, etc.

But, wait? A deity is no “real person”. How can he/she enjoy this property? Well, if the law can recognize the personhood of a body corporate (a company), its right to own property & transact in its own name, nothing ought to prevent a similar recognition in the case of temples.

There is a long, historical precedent (from both texts & inscriptions) allowing the recognition of a deity’s legal personhood, full ownership of its residence (& other properties) & freedom to decide how the residence ought to be accessed or enjoyed by other persons.

In accordance with what is the deity’s will executed & implemented by the priests and/or management who are both, verily, the deity’s trustees? The Agama-s or relevant tantra-s or paddhati-s known to govern the temple from very inception or simply known as last remembered usage.

Some idiot Hindus stated that the argument that shrI dharmashAstA in his form as ayyappa is observing naiSThika brahmacharya is not a sensible one as it suggests that ayyappa is “unable to see his women devotees in the 10-50 age group as sisters or mothers”.

Again and again, Hindus excel at showing mediocre quality of thought. Firstly, the mythos and rituals associated with a particular temple are not meant to be read as physical realities and anthropomorphic qualities are not be superimposed on the deity.

Our deities have transcendental and most subtle bodies. They do not “eat offerings” or “observe brahmacaryam” in the same way mortals would be seen in our mundane level of reality. Rituals and myths operate at a higher level of reality. What is the significance of this?

Well, this is the significance:

This is how our ritual spaces work and something I hope can be drilled into the heads of the judges who have no erudition about our religion. The deity’s nature (in Southern Agamika & tAntrika temples, this is based on the mantra-s installed in the deity’s icon/vigraha), location of deity’s shrine, nature of rituals done, type of priesthood, kind of food and flower offerings made to deity, nature of people who come to the temple, colors of garments worn by the deity, priests & devotees & many other factors all have to cohere with one another as far as possible.

All these factors come together to create a coherent “ritual reality”, which is the ultimate fruit a sincere worshiper truly yearns for. The deity’s presence becomes fully manifest and becomes a source of blessings for the worshipers and their families. Different Agama-s and tantra-s have their own versions of the “ritual reality” or “ritual universe” they are asking the priests and others to enact on this earth.

An example of this logic of ritual coherence: The shaiva Agama, kAmikAgama states that the fierce forms of both shiva & viSNu should be installed at village/town outskirts & not in the interior. Why so??

This choice of location (outskirts) matches with deity’s fierce nature, as that which is fierce & potentially dangerous must naturally be away from the dwellings of men. So, in the cases of temples & towns planned/designed in accordance with kAmikAgama, this will be the rule.

The idea of ritual coherence operates at sabarimala too. The mantra-s installed in that ayyappa mUrti in times of yore embody the naiSThika brahmacAryatvam (permanent celibacy) intrinsic to that deity. This is the essential nature of the deity; his “essential ritual reality”.

The “ritual reality” of a temple is harmed or even destroyed when the stipulated rules in place are not respected. In this case, the relevant rule would be the prohibition on the entry of women having reproductive abilities.

Such an entry alters & disrupts the “ritual reality” the temple seeks to manifest in this world. The concepts of “ritual reality” & “ritual coherence” lie behind our idea of “ritual space”. What may be appropriate in one sacred space may be completely inappropriate for another.

Example: In the shaivAgama-s, the presence of rudrakanyA-s. These young, pious virgin girls devoted to shiva perform dances in front of him & are even invited, along with the priests & king to be the very 1st recipients of the divine glance of a newly consecrated shiva!)

This would not be the case for the ritual space of ayyappa. The women would have to wait till certain biologically innate characteristics are gone with age, before seeking to visit ayyappa.

This is nothing to do with ayyappa’s “mind” as some idiots wrongly understand, Nothing can upset or agitate the mind of a transcendental being. But when the same transcendental being is installed in an icon with mantra-s, etc, certain formalities come into effect.

Another verse on the sadāśiva residing at cidambara

Introduction:

Only the first word (எல்லையற்ற/ ऎल्लैयऱ्ऱ /ellaiyaṟṟa) of the below verse was reverberating in my mind. But even as I decided to go to the gym nearby and work out, the first word would not leave the consciousness.

எல்லையற்ற மறைக்கொப்ப நுண்ணிய இனிமிகு துறைனூலதன்

சொல்லைகுற்ற மென்பார் விழியாகும் ஒருவழியார்க்கன்பர்

இல்லைசுற்ற மொருவன் மூவராகுமெழில்மிடறன் முச்சிக்குளிர

தில்லைசிற்ற அம்பலத்தில் எண்தோளர்க்கெண்தோழர் செய்வாரே

ऎल्लैयऱ्ऱ मऱैक्कॊप्प नुण्णिय इऩिमिगु तुऱैऩूलदऩ्

चॊल्लैकुऱ्ऱ मॆऩ्पार् विऴियागुम् ऒरुवऴियार्क्कऩ्बर्

इल्लैचुऱ्ऱ मॊरुवऩ् मूवरागुमॆऴिल्मिडऱऩ् मुच्चिक्कुळिर

तिल्लैचिऱ्ऱ अम्बलत्तिल् ऎण्तोळर्क्कॆण्तोऴर् चॆय्वारे

ellaiyaṟṟa maṟaikkoppa nuṇṇiya iṉimigu tuṟaiṉūladaṉ

collaikuṟṟa meṉpār viḻiyāgum oruvaḻiyārkkaṉbar

illaicuṟṟa moruvaṉ mūvarāgumeḻilmiḍaṟaṉ muccikkuḷira

tillaiciṟṟa ambalattil eṇtōḷarkkeṇtōḻar ceyvārē

Whole English translation:

He who calls flawed the word of the books of the subtle, very sweet path, [the books] which equal the limitless veda; he is not a devotee of one who, guiding on a path, becomes, [as if], an eye /

[There is only] one kinsman, one bandhu. In the cidambara temple at tillai, the eight companions of the eight-shouldered one caused the top-knot of the one, of a beautiful neck, who becomes the triad, to cool [with abhiṣeka]!! //

More detailed meaning:

எல்லையற்ற/ellaiyaṟṟa: Without limit/end, limitless/endless

மறைக்கொப்ப/maṟaikkoppa: equaling the veda.

Note: In the śruti, it is said, “anantā vai vedāḥ” (taittirīya brāhmaṇa 3.10.11.4). Such limitless/endless veda; equaling that (in greatness)

நுண்ணிய/nuṇṇiya-subtle

இனிமிகு/iṉimigu-very sweet/very good

துறைனூலதன்/tuṟaiṉūlataṉ-Of those books of the tuṟai (tuṟai here is referring to śivadharma/siddhānta; the books of the tuṟai are the books of the siddhānta path: the siddhānta āgama-s)

Note: The word துறை/tuṟai in tamiḻ can be used used in the sense of dharma. In periyapurāṇam, when describing the purpose of the birth of the child-saint jñānasambandha, it is said: வேத நெறி தழைத்தோங்க மிகு சைவத்துறை விளங்க. துறை/tuṟai here means “ford”; as in, a point at which a river or stream can be crossed or used for taking a bath, etc. Here, jñānasambandha’s advent is said to have been for the purpose of the flourishing of the veda dharma and the shining of the śaiva “tuṟai”, that is śivadharma, the way of the siddhānta. Additionally, do note that the ford imagery to describe śaivam (siddhānta) goes well with the characterization of the five streams (pañcasrotāṃsi), of which the siddhānta is one and is, obviously, deemed by the saiddhāntika-s as the ūrdhvasrotas (the upper stream-i.e. the highest).

tuṟaiṉūl: The book/books of the tuṟai. What are the texts of the siddhānta? The siddhānta āgama-s, of course. The āgama-s equal to the limitless veda.

tuṟaiṉūladaṉ-of those texts of the tuṟai; of those siddhānta āgama-s

சொல்லைகுற்ற மென்பார்/ collaikuṟṟa meṉpār: Those who call as flawed the word/words [of the aforementioned texts, the siddhānta āgama-s]

விழியாகும் ஒருவழியார்க்கன்பர் இல்லை / viḻiyāgum oruvaḻiyārkkaṉbar illai: he (the aforementioned person reviling the āgama-s) is not a devotee [or rather, not fit to be a devotee] of one who, guiding on a path, becomes, [as if], an eye.

Note: Who is the one who guides on a path and becomes, as if, an eye to the person being guided? The ācārya, of course; he who guides a soul to śiva. வழியார் / vaḻiyār here means the one on/of the path. வழி / vaḻi means way/path. There is a deeper meaning behind the use of two adjectives to describe a single person (the ācārya), and that too, similar sounding words: vaḻi (path) and viḻi (eye), which will become apparent towards the end of this article.

சுற்ற மொருவன் / cuṟṟa moruvaṉ: One is the kinsman/bandhu.

Note: This refers, of course, to sadāśiva, who is with an ātma for all time, while the soul’s form (it takes when incarnating), his parents, his friends, his place of birth, his characteristics, etc are changing. The permanency of the relationship between sadāśiva and the ātma is indicated here.

மூவராகுமெழில்மிடறன் / mūvarāgumeḻilmiḍaṟaṉ: He, of the beautiful neck, who becomes the triad

Note: The term has to be split as மூவராகும் / mūvarāgum + எழில்மிடறன் / eḻilmiḍaṟaṉ. mūvar means triad here. mūvarāgum means “becomes the triad”. eḻilmiḍaṟaṉ means “he of the beautiful neck” (மிடறு / miḍaṟu means neck)

முச்சிக்குளிர/muccikkuḷira: [cause] the top-knot of [the one, of the beautiful neck, who became the triad] to cool

This has to be read together with the previous phrase.

தில்லைசிற்ற அம்பலத்தில் / tillaiciṟṟa ambalattil: In tillai, in the cidambara [temple]

எண்தோளர்க்கெண்தோழர் செய்வாரே / eṇtōḷarkkeṇtōḻar ceyvārē: The eight companions of the eight-shouldered one will do.

Note: What will they do? They will cause the supreme sadāśiva to cool, from head to foot; all the way from the top-knot on his head. The last word, செய்வாரே / ceyvārē must be read together with முச்சிக்குளிர/muccikkuḷira. So, rearranging, the verbal phrase is as follows:

முச்சிக்குளிர செய்வாரே / muccikkuḷira ceyvārē : They will cause his top-knot to cool [by performing abhiṣeka with water and other unguents].

Why is the deity described as eight-shouldered here? The term for his being eight-shouldered comes right from the devāram, where the hallowed tamiḻ poets describe him as eight-shouldered. The simplest explanation is that the supreme deity, sadāśiva has five heads, with four heads facing in the four cardinal directions while the fifth is on top of the four heads, facing upwards. The two shoulders for each of the four cardinal faces add up to eight.

Thus ends the literal translation. A hidden meaning has been left behind for those interested in reading this article till the end.

Now, the obvious question is that who are these eight companions, who perform abhiṣeka to sadāśiva, residing in that pristine temple of cidambara?

See, there was an inextinguishable urging inside me for the past several days to write a verse in tamiḻ on the eight vidyeśvara-s. “How can their names be found in a text written partially in Old Javanese (related to the Malay of my own homeland, siṁhapurī) but not be found in a single tamiḻ work of note, especially when drāviḍadeśa is the only place where the siddhānta tradition really thrives?” See here for a note on the presence of saiddhāntika tradition as far as Java. It seemed rather blameworthy and I sought to rectify what I perceived as a deficiency.

These are the aṣṭavidyeśvarāḥ and this is a fixed order of their hierarchical ranks, with ananta being the highest of all the 8 vidyeśvara-s and second to sadāśiva only, and śikhaṇḍin being the last of all the vidyeśvara-s.

1. ananta (infinite, endless, limitless)

2. sūkṣma (subtle)

3. śivatama/śivottama (most gracious/most auspicious)

4. ekanetra (Literally, one-eyed, but netra also means leader

5. ekarudra (one rudra)

6. trimūrti (three forms)

7. śrīkaṇṭha (beautiful/radiant neck)

8. śikhaṇḍin (one with a śikhā)

These eight effulgent and exalted beings, though not directly named in the above verse, have been subtly indicated, without doing violence to the hierarchical order. See:

எல்லையற்ற / ellaiyaṟṟa (limitless): ananta

நுண்ணிய / nuṇṇiya (subtle): sūkṣma

இனிமிகு / iṉimigu (very sweet/good/kind/pleasant): shivatama/shivottama

விழியாகும் ஒரு வழியார்க்கு / viḻiyāgum oru vaḻiyārkku (The guide on the path who becomes an eye): ekanetra (netra means both eye and leader. The word “oru”, meaning one, is to emphasize the “eka” in ekanetra)

சுற்ற மொருவன் / cuṟṟa moruvaṉ (the kinsman is one): ekarudra. This is in reference to the story from the śatapatha brāhmaṇa from the veda where prajāpati was abandoned by the deva-s, and only rudra in the form of manyu remained within him and manifested as hundred-headed, thousand-eyed form. The singular term “oruvan” here is to emphasize the “eka” in ekarudra, as “oru” did for ekanetra.

Note: Today, I was struck by an alternative for சுற்ற / cuṟṟa. The word கொற்றன் / koṟṟaṉ meaning victor. In that case, the reading will be கொற்ற னொருவன்.

மூவராகும் / mūvarāgum (he who becomes the three): trimūrti

எழில்மிடறன் / eḻilmiḍaṟaṉ (he of the beautiful neck): śrīkaṇṭha who is of the beautiful neck.

முச்சி / mucci (top-knot/ śikhā): śikhaṇḍin who sports a śikhā.

Thus, all eight vidyeśvara-s have been indicated indirectly. Towards the completion of the verse, I had an imaginative vision in my mind, where the eight vidyeśvara-s are performing abhiṣeka to the deity of cidambara.

Text as Text, Text as Deity: Reconciling Ritual Rules of Textual Traditions with Devotion to the Gods

Note: Recently, I submitted an essay with the above title for a biannual journal on polytheism, Walking the Worlds, for the Winter issue of 2017, as you can see here. I am making the essay available in this blog for interested readers from Twitter and elsewhere. Hindu friends, do note that the journal is targeted at a primarily Western audience, and hence I had to write a comprehensive introduction. The essay can be read here:

Sectarian ADambara in Internet Hinduverse: More noisy than jayanta bhaTTa’s AgamADambara & not nearly as insightful or constructive

Context: https://twitter.com/MadhvaHistory/status/959408605152739329

1. A brief note for those interested in learning rather than sectarianism: The attempt by abrahma-s to study mAdhva-s or rAmAnuja-s should be understood carefully. It should NOT be understood as mAdhva-s sharing some features with abrahma-s; which is clearly superficial

2. Understanding mAdhva-s & abrahma-s as “sharing” them gives a false impression that these so-called “shared” features independently originated among abrahma-s, or are an original insight by them, & therefore the mAdhva-s too have evolved in a similar pattern as the abrahma-s.

3. So, for instance, let’s take one such “shared” feature, that brahman is only an effective cause (nimitta kAraNa) & not the material cause (upAdAna kAraNa) of the universe. Of the 3 major schools of vedAnta, only mAdhva-s argue this. The rAmAnuja-s & advaitin-s argue otherwise.

4. This is one feature that attracted abrahma attention to mAdhva-s. However, mAdhva-s aren’t the only ones to boldly depart themselves from prevailing scene in vedAnta. The shaiva siddhAntin-s have been arguing exactly the same point since their time at kAshmIra in the 600-s.

5. So, even within dharma, there is a great diversity of opinion. So, this is not exactly an outlying opinion. The abrahma-s find this similarity appealing as it suits their purposes. That is all. They hold that their “God” (not our brahman) & the universe are not made of same material.

6. The abrahma-s are not original for having this opinion. Virtually, every non-abrahamic system predating the abrahma-s in those lands has understood the creator or the gods being the efficient cause of the universe only, not as being the material cause.

7. In other words, to put it simply, both abrahma-s & mAdhva-s have taken an idea which predated both & was already appreciated by the non-abrahamic world for a long, long time. In fact, it’s the more natural idea for vast majority to understand (though my own birth sampradAya varies from this position🙂)

8. So, it’s clear why framing this as an example of a mAdhva “closeness” or similarity to abrahma durmata would not be a proper position to take at all.

9. Another example I will quickly dispose of is one about avatAra. Actually, most abrahma-s will virulently reject the idea that their “divine” rAkSasa can take birth. We are left with the preta-s.

10. The preta theology, if anyone bothered to study, had the “Incarnation” as the fundamentally most significant theological point. Some preta-s saw a parallel with the avatAra concept but saw that it was particularly important to vaiSNava-s. But how similar are these?

11. No.1: The avatAra-s are accepted by all sects of our dharma even though they may not occupy the same level of importance for all of them. No.2: The significance of the ‘Incarnation’ of the preta is because of the abrahma view of history as essentially linear & finite.

12. In other words, the 2000-year-old birth of the preta from a “kanyA” under suspicious circumstances was an irreversible turning point in history. It is the fulcrum about which all of time before & after it revolves. One’s eternal fate hinges on this historical event.

13. Our avatAra-s, despite their immense importance, are ultimately part of a cyclical framework for the vast majority of the traditional schools. The same avatAra-s may not repeat in another yuga or manvantara or kalpa.

14. Finally, while the idea of gods incarnating as humans is quite rare, it is not completely unknown outside the Indic & abrahma spheres. The Aztec god Quetzalcoatl as the human ruler Topiltzin or Thoth/Hermes incarnating as Hermes Trismegistus are examples.

15. Ultimately, there are only two options. Either the divines (or a part of them) can be born on earth or they cannot. All of mainstream Hinduism asserts that they can. To find similarity between vaiSNava-s (not just mAdhva-s) & abrahma-s is a technique of abrahma cunningness/dishonesty.

16. So, those two examples give some idea of why making comparisons between abrahma-s and our own folks (whatever sampradaya they may be) is something that requires immense caution and nuance.

17. As someone who has consistently honoured a variety of sects & traditions within dharma, as someone who actually tweets in honor of both the rAmAnuja and mAdhva AcArya-s, as someone who repeatedly tries his best to work beyond sectarian divisions, I do have a request though. Care to read further?

Request:

It’s very easy to call for Hindu unity. It’s very easy to put Hindu interests first when one is in the comfort zone, and nobody has said anything controversial, mistaken or misguided.

But it is very difficult to harden the heart and put Hindu interests above sampradAya pride/zeal when that conflict comes. I respect many of the people of other sects than my own. Many of you are excellent handles, tweeting valuable and wonderful information. But how quickly one person’s mistaken observation was extended to “an understanding of Dvaita by fellow schools of Vedanta”?!

Immediately in response to the linked tweet above, one sees a “Just another advaitin showing off his mithyaj~nAna” or a crass remark like this: https://twitter.com/venkatsobers/status/959415525695631361

My Request to @Madhvahistory and other level-headed individuals like him: Those hurt at their sect being compared to something unfavorable (comparison is WRONG, superficial & ignores technicalities), I hope you’ll also help rein in your folks when they diss other AcArya-s or post hurtful hagiographic stories belittling followers of other deva-s.